Women-as-dragon, as a concept, has been around since ancient times. In Greek myth creatures like Scylla, Echidna, and Medusa had monstrous or dragon-like aspects, as did Grendel’s mom from Beowulf. Norse myth spoke of the dragon Nidhogg that gnawed at the roots of the World Tree Yggdrasil. And of course, there’s Lilith and Tanit/Inanana/Ishtar. They have over time gone from being creatures of power to being cursed and outcast.

In Western fantasy literature fairy tales formed the bulk of dragon transformations up until this century. One of the most typical is the ballad The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh. An evil Queen, jealous of the beauty of her stepdaughter Margaret, turns her into a dragon. When her brother Childe Wynd returns from overseas, Margaret tells him that to break the spell, he must kiss her loathsome form. Unhesitatingly, he does so, and she turns back into a human. Together, they overthrow the Queen.

This is an Arthur Rackham illustration I remember well from a book of fairy tales I had as a child. Arthur Rackham can be thought of as the inspiration for Brian Froud. I think he intended this dragon-serpent to look repulsive, but she’s actually pretty cute with her nose in the air.

In this pic the Lady Margaret is emerging from the skin of the worm, or wyrm, in a manner similar to St. Margaret who may be her inspiration. But unlike St. Margaret, she is saved by the dedication of a man and not God. Actually, it’s more than dedication. It’s a willingness to face the dark and unpleasant things in life.

A dragon masquerade in the 1910s.

In the 1960s Disney animated cartoon Sleeping Beauty the villainess Maleficent makes a powerful inspirational turn when she transforms into a dragon to thwart Prince Phillip. I think it’s the first time “Hell,” that most minor of cuss words, was uttered in a children’s movie.

What this says as a myth about gender relations is interesting. Aurora and Maleficent can be argued to be two sides of the same woman. The pretty, feminine, submissive Aurora sleeps; the active, evil, powerful Maleficent guards her and prevents her from waking. When the Prince comes, Maleficent pours all her wrath into fending him off. Yet in the end she is defeated, and Aurora woken with a kiss, and taken away into traditional married life. It can be read as an indictment of women’s’ lives in the 1960s, where they were expected to give up their autonomy and power to be traditional wedded wives. But perhaps it can also be read as a sexual awakening, where a woman’s fear must be defeated for sexual unity and enjoyment to take place. The movie was made in 1959, on the cusp of the 1960s and its social changes. It seems to predict the battle of the sexes. If Prince Phillip symbolized traditional roles, he ultimatelywon the battle but lost the war.

In Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Tombs of Atuan there’s a similar situation, described by the author herself as “puberty” where Tenar has the power to kill and defeat Ged, yet restrains from it because of her pity and fascination. She gives him water and the directions to get out of the labyrinth, and he later emerges to be the cause of an earthquake that collapses much of Tenar’s old home and whisks her away to become “The White Lady” in the inner archipelago, a traditional patriarchy where she is to be powerless, yet exalted, in a fine silk gown. Was I the only one who felt let down by this ending?

Over the decades Maleficent has gradually become the apex Disney villainess and something of a role model for many modern women for her evil glamour and ruthlessness. She is so popular she even recieved a retcon in the 2014 movie Maleficent, with Angelina Jolie in the title role. Disappointingly, it’s her henchman that turns into a dragon, not Maleficent herself, but she does have a pair of horns and hooked, dragonlike wings.

Dragon women also received a strong boost from the 1984 American TV show V, which had the Earth conquered by a race of reptile people who masqueraded as benevolent human overlords. Two of the most prominent were Diana (Jane Badler) and Lydia (June Chadwick), commanders of the invading “Visitor” forces. Described as chaotic evil and lawful evil, respectably, they paraded around in form-fitting uniforms and did naughty things like eating live mice. The show was a turning point in SF. Up to that point, women had not been portrayed as leaders in SF worlds; even Star Trek: The Next Generation, for all its fanfare and emphasis on diversity and equality, still had male captains. The two powerful lizard women inspired a lot of frenzied wish fulfillment for girls of that era.

Behold the awesome, futuristic plywood console for advanced spaceship navigation.

|

|

It seems the rock band KISS was an influence on the costume designers of the show. In the photo at the console Diana’s uniform bears a distinct resemblance to Ace Frehley’s Space Ace getup, and in one episode the ladies even don a variant of his facepaint (above, left.) Tragically, the full-blown lizard prosthetics were rarely shown, and then only in pieces (above, right.)

In the years since V, other Dragon girls have cropped up in unlikely areas. In the comic world, for example, there is a zaftig character called She-Dragon, who seems like a She-Hulk knockoff.

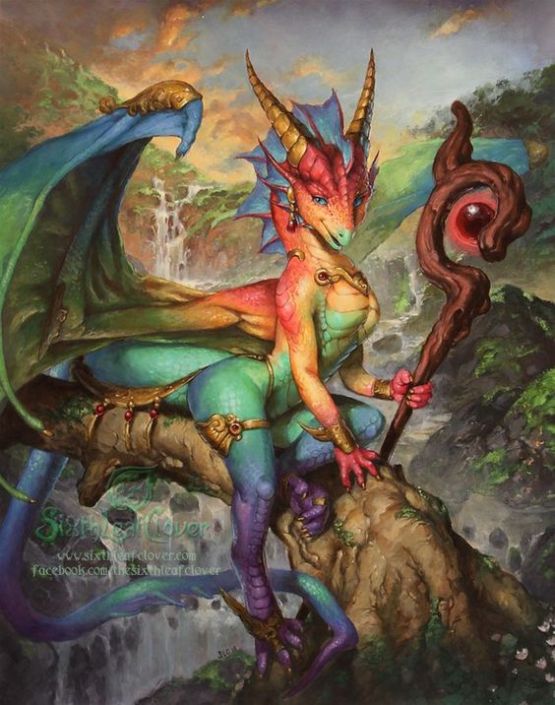

With the rise of the internet, it became easier than ever for SFF artists to scan and share their work, and fans to share artwork and fiction too, and their fantasies, and find connection with other fans. That’s how Furries founded a subculture. Furries are folks interested in humanoid and anthropomorphic animal characters as creators of artwork, fans, or roleplayers. Deviant Art, founded in 2000, became a major online site for Furry connection and artistic critique. The most popular Furries have traditionally been the glamourous ones like big cats and wolves, but as with fanfic writers, artists continually push the barriers of what is possible, and thus, Dragon girls were born… sexy, dangerous, intriguing creatures of fantasy.

So we have come full circle over thousands of years. Dragon September is over. It’s been fun!