(The following art essay is created from my Lady and the Dragon posts of September 2018. with some slight changes, corrections, and additional material.)

For most of the Western world dragons have been long been creatures of evil and corruption, yet modern artists are making them over into blazing paragons of female beauty. How I would have loved to see this in my childhood! I had always liked dragons, to the extent of identifying with these creatures in make-believe games. And why not? They were singular and powerful. That artists are now making the fantasy come alive has been a revelation.

I can tell you back then it was not kosher to be in love with dragons the way these artists are today. Sure, there were dragons around. The association of the dragon with evil was beginning to soften in the 1960s, with the children’s song Puff the Magic Dragon by Peter Paul and Mary, and Ollie the dopey one-fanged dragon from the puppet show Kukla, Fran and Ollie. Cecil the Sea Serpent from the Cecil and Beanie cartoon was dragon-like in appearance if not exactly a dragon. Disney too contributed sympathetic dragons, such as the title character of The Reluctant Dragon. But, these were all male. Female dragons were left out of the mix, save for Maleficent’s magnificent transformation in Sleeping Beauty. In contrast the others, she was… bad. Very bad. And all the more alluring for it.

Where did this association of female dragons with evil come from?

In the Biblical story of Adam and Eve, the Serpent, the tempter, is never explicitly defined as Satan in the text. A Jewish text written later in the 7th century, Alphabet of Sirach, identifies the Serpent as Lilith, Adam’s first wife, who left him for expecting her to “lie beneath” him during sex (that is, be subservient) to him. Seeking revenge on God and Adam, the story goes, Lilith turned herself into a serpent to tempt Eve into corruption. Many Medieval paintings of Eden reference this legend, giving the Serpent a woman’s head. I can see why. Visually, it’s more interesting. Genesis also hints the Serpent loses its legs over the incident, so in addition to having a woman’s head, the Serpent has two or sometimes four limbs and becomes a lizard-like or dragon-like creature. Adding to the confusion, serpent and dragon are often used interchangeably in the Bible as synonyms for evil, so Serpent-Lilith becomes a female dragon. To make things even more complicated, the original story may have been written as satire, not religious dogma… the early Medieval equivalent of Woody Allen.

Adam and Eve committing original sin, detail from The Virgin of Victory, 1496, by Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), tempera on canvas, 280×166 cm.

Serpent-as-Lilith has a woman’s face here, but her hair is more stylized, like a sculpture of the Green Man motif common on European fountains.

In this illustration from a Medieval Book of Hours Serpent-as-Lilith has breasts, a scaled body, and two clawed feet, giving her a wyvern-like appearance. Her lower body seems very sculptural, like what is termed a Grotesque in Baroque art.

The Serpent has become a strange cockatrice-like monster in this German depiction, but with Lilith’s head.

Hugo van der Goes, The Fall of Man and The Lamentation, 1470 – 1475

Lilith has become a platypus-like creature in this luscious, yet awkward, rendition by Hugo van der Goes. Or maybe an otter? She’s kind of endearing.

But the meaning of the artwork is all too clear. “Bad” women corrupt as dragons poison and corrupt, as dragons were wont to do in the ancient world. “Bad” means disobedience. “Good” women are pure, ignorant, and should be obedient to men, even if Eve wasn’t. Some artists took things further by depicting Lilith with black hair (non-white) and Eve with blonde hair (white and pure.) C. L. Moore’s classic short story “Fruit of Knowledge” uses this trope. It’s available to read online.

And why did Adam have two wives? Because there were two Genesis stories of Mankind’s creation! Because the Bible was the literal word of God, they both had to be true, right?

Getting back to Lilith, scholars have traced her origin to ancient Mesopotamia, where the lilitu were female demons. The goddesses of Tanit, Innana and Ishtar, belonging to nations of pagans that were enemies at one time of the Jewish people, were also incorporated into her character, and so begins the strong-woman-as-demon trope… blah blah blah virginwhorecakes.

But Lilith has had the last laugh. A series of influential music festivals has been named after her! All Eve has is a douche and a forgotten brand of cigarettes.

Burney Relief, Southern Mesopotamia, 1800 – 1750 BCE

The goddess depicted on this plaque may be Lilith, Ereshkigal, Ishtar, or Inana; no one knows for sure. She has a dragonlike appearance almost akin to a modern anthro Dragon Girl, though her feet and wings are actually thought to be avian, perhaps those of the owl with which she is associated. Still it’s a powerful image, full of female power… and supremely predatory.

Moving on to the rise of Christianity, it’s interesting to note that dragons are usually accompanied by women, not men. Here’s some examples.

A common depiction of Mary, Mother of God, shows her trampling a snake (keep in mind snake=dragon in Biblical text) underfoot, representing her victory over the Devil, or over evil in general. But now that I know about the Lilith connection, I’m reminded of how virtuous Eve has gotten the ultimate prize — Adam — and prevailed over her unctuous rival.

A plaster statue of Mary resided in my bedroom for the longest time, and I always felt sorry for that snake even though I knew it was probably blasphemy. It looked so small and defenseless. One day I went to move my bureau and the statue toppled down and smashed into pieces on the floor. I truly thought I was going to go to hell because I had killed the Virgin Mary.

St. Margaret is another female saint with a dragon connection. She was born in Antioch to pagan parents, but was converted to Christianity by her nurse. When a Roman governor wished to marry her she refused, not wanting to give up her faith or her virginity. In response, he imprisoned her and tortured her, one of the highlights of which was her being devoured by Satan who had taken the form of a dragon. The cross she carried, however, irritated his stomach, and he “burst asunder,” allowing her to escape.

Though the last part of the tale wasn’t taken seriously by the Church even in its fanciful Medieval days, it proved a great inspiration to artists. You have to admit it made for a more memorable depiction than showing her herding sheep or praying, the other activities she was noted for. It allowed them to riff on what makes a convincing dragon, and how such an animal would look if a human being suddenly exploded from its insides. The picture to the left shows the dragon, which is depicted as a winged snake like Quetzalcoatl, being cut cleanly in two.

This dragon has wings attached to its forelegs and a wild boar’s head. In common with many depictions of this legend, its size is far too small to contain a human being in its stomach. St. Margaret looks like she is weeping from relief, or maybe, fright at escaping her tiny prison while the dragon looks unperturbed.

Here it’s the dragon who looks wide-eyed with shock and fright. He still hasn’t swallowed the train of her dress before she bursts free. The dragon’s pekingese dog face, furry, floppy ears, and unicorn horn may refer to another layer of symbolism, or be artistic invention. I interpret the expression on Mary’s face as “Told ya so.”

The dragon here looks nauseated as Margaret emerges amidst blood and gore. Again he hasn’t had time to swallow the rest of her gown which is far too long for a normal garment. All of these depictions seem to me to say: A woman can escape from her own dragonish nature if she holds faith in God.

Finally, there’s St. George, the originator of the ages-old damsel-in-distress trope. Knight kills dragon who holds a princess captive, and then he marries the princess. But in looking at Medieval depictions, it seems a different story is being told.

Saint George and the Dragon by Rogier van der Weydon

The princess kneels in the distance here, away from the action. She could run away, but she doesn’t. Instead, she chooses to pray. She and the dragon have some connection other than physical that is compelling her to stay put. Maybe… she and the dragon are actually the same being? The knight on his tiny-headed gelding is slaying her independent, aggressive dragon nature?

Saint George and the Dragon by Paolo Uccello

The princess is physically closer to the dragon in this portrayal, but she looks like she is leading it on a leash, like a faithful hound, rather than being chained to it like the artist intended. Either way, it’s a closer connection. She is not praying here and appears somewhat bored. The knight slays this dragon by piercing it through a nostril, like one would a wild boar or bull. It’s a spindly, rickety-looking beast that doesn’t seem like much of a threat, despite its fangs and claws. Its looks anguished, and I feel for it.

Again, the princess’s wild, dragonish nature must be overcome before she gets her man (or is awarded to him.) But in the symbolic nature of this legend, it’s the duty of the knight to do this, not the princess.

It’s important to note that before the printing press and paper production on an industrial scale there were very few mass-produced dragon depictions in popular culture. Most of the ones I referenced above were oil paintings intended for the nobility or wealthy merchants. The majority of medieval citizenry lacked such portrayals, crude as they were. If they were lucky they might see some dragons as part of the artwork of their local cathedral, or on crude block prints sold for decorative use.

In the 19th century, when book production took off as part of the industrial revolution, depictions began to filter down to the masses. Many of them were based on, or reproduced, older art. Detailed metal engravings were common for the printing industry of the time.

Jason and the Dragon (1765 – Etching / Engraving) by John Boydell, after Salvator Rosa

In the early decades of the 20th century printing and paper making technology enabled the production of the cheap mass market literature known as pulp, or the pulps, called that for the paper it was printed on, made of wood pulp that yellowed easily and quickly decayed. Pulp also well described its subject matter, which was sensationalistic – early science fiction and fantasy, detectives and police stories, horror. With the addition of a growing children’s literature market, dragon portrayals began a mass dissemination into popular culture.

For children, most of these portrayals were from fairy tales, the imperiled princess and rescuing knight kind, but without the religious piety. The adult side had the female figure mostly being captured or menaced by various BEMs (bug eyed monsters) in addition to dragons and other reptilian creatures. The female was often contorted, clutched, or crawling on the ground as the hero rushes to protect her.

But. In a new strain of fantasy fiction, typified by the Barsoom series by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the princess is an active participant in these adventures, sometimes even wielding a sword and fighting alongside the hero.

Jongor Fights Back, by Frank Frazetta

OK, this dragon is more like a giant lizard. But in the 1960s, when Frazetta painted this, we can see a change taking place. Though the girl is hanging for dear life, she’s not screaming or clutching at the male as in earlier pulp depictions. She’s looking around, as if scouting, alerting the archer to attackers. Most importantly, she is riding a dragon.

In his career Frazetta painted many woman hanging around with giant wolves, snakes, demons, and other dire beings, so this was just part and parcel of that, and it’s probably not the first woman riding a dragon on the cover of a pulp fantasy book, either. But Frazetta was the most influential fantasy artist of the time, and his covers were in constant demand and constantly visible, often being re-used for different titles. More importantly, they were also being reproduced as art prints.

Anne McCaffrey’s Pern books introduced the female dragonrider with more fanfare in the late 1960s, even though the early covers did not actually feature Lessa on her dragon. By the early 1970s, they did.

But before the first Pern story was published in Analog, there was a woman that rode a dragon, in a Hanna Barbera cartoon called The Herculoids no less, on Saturday morning.

I loved this cartoon as a small child because of that dragon, whose name was Zok, whom I took to be a female (I was let down when I began paying more attention to the dialogue and realized the other characters referred to it as a he) and though the stories were very basic – barbarian family on strange planet is besieged by aliens, then defeats them with the help of their giant pets – cringingly so if watched today – I loved that dragon, who in addition to shooting rays from its catlike eyes, could whip its tail around in midflight to shoot yet more rays from its tip. Tara, the generic female of the barbarian family, was mostly useless, prone to being kidnapped and then rescued by Sandor, her husband, but occasionally she entered the action riding one of the beasts, usually Zok, to attack.

Since Alex Toth, the creator of these characters, came from the comic world, I’m sure there are dragon-riding women buried elsewhere in the comics of this age. He passed away at the age of 78, at his drawing table, still creating art. Now that’s an artist!

There was also this singular image from a groooovy black light poster produced in the early 1970s.

I first saw this poster in a friend’s brother’s bedroom in Hawaii and I remember staring at it in fascination. Her mom would always shoo me out, because they were a military family and the brother was away at basic training, or something, but I would continue to sneak in, and stare, when I could. This brother also had a taxidermied cobra emerging from a basket, and I would stare at that, too.

The poster is a hippy product, no doubt, and the female dragonrider has a man behind her, which had vanished from my memory over the years. But she is riding it, even if the man seems to be teaching her, and the dragon is fierce. I wonder if its creator had read the Pern books, or been influenced by comic art. Or perhaps there was some Mucha-influenced girl and dragon combo on a Bay Area rock poster.

A few years later Jefferson Starship contributed this amazing album cover.

The picture plays a pun with dragon and dragon lady (probably a now-racist term for a sexy, powerful Oriental woman). The dragon is snarling, but clearly under the control of its rider, who seems to be creating it with the smoke from her pipe. “Chasing the dragon” is slang for smoking opium, so perhaps she is dreaming up this ferocious mount? The artwork was created by Japanese artist Shusei Nagaoka, who also did covers for Electric Light Orchestra and Earth, Wind, and Fire.

Portrayals of women with dragons continued to rise throughout the 1970s, boosted by the rising genre of adult comics, forerunners to today’s graphic novels. The French magazine Metal Hurlant (Howling Metal) showcased many of these new artists like Caza, Alejandro Jodorowsky, and Moebius, many of whom went on to design book covers and production design. Two years later an American version of Metal Hurlant was licensed and renamed Heavy Metal. Adult comics as defined by both versions of Heavy Metal meant more artistic sophistication as well as more gore, sex, nudity, and a kind of dumb, counterculture cynicism. And let’s be frank, “adult” in this context meant plenty of female objectification as well (the editors of America’s National Lampoon magazine were the ones who shipped Heavy Metal over the Atlantic, after all.) A common subject matter for covers was an over endowed woman posing with or riding some fantastic beast. Yet it also showed women as singular, powerful warriors.

Artwork by Chris Achilleos, 1980. Very early in his career.

This Heavy Metal image, adapted later for the promo campaign of the animated movie of the same name, by artist Chris Achilleos shows the popular character Taarna on her dragon, which is a pterosaur-like creature originally created by Moebius. It’s a pose that harkens back to the hippie black light poster, but this time the woman wields a sword and wears leather armor. She’s out for business. In the movie this image advertises, she doesn’t even speak. She’s a solitary avenger, unlike Pern’s Lessa who is embedded within a social matrix of dragonriders. Though a leader and organizer, Lessa was not a fighter, and she became who she was only by virtue of being bonded to a fertile female dragon, Ramoth. Taarna exists by herself. I can’t help but feel this speaks to the rising status of women in the seventies.

Luis Royo’s version of Taarna, who is posing somewhat lacklusterly. Royo also did artwork for Heavy Metal, as did many SFF and comics artists like William Stout, Jim Burns, Angus McKie, Sanjulian, Greg Hildebrandt and Charles Burns.

The dragon-riding female warrior had entered the 1980s with a bang.

Artist Boris Vallejo seems to be poking gentle fun at the trope with this portrayal. The nude riders are impossibly lithe and tanned, yet still deadly serious as they ride without saddles or seatbelts.

In popular culture a new dragon rider arrived on the scene in the early 1980s: Kitiara and her Blue Dragon, Skie. Kitiara was a character in the Dragonlance series of novels written by Margaret Weis and Tracey Hickman, the first books carrying the TSR novel imprint using AD&D themes and monsters. The books were generated from a massive roleplaying session of the Dragonlance gaming modules, which author Tracy Hickman had developed together with his wife Laura Hickman. The purpose of the Dragonlance modules was to highlight the ten dragon types as the core monsters of the game, which TSR felt the game was moving away from.

Kiriara, Skie, and Kender Tasslehoff Burrfoot. Note that Skie does not conform to Blue dragon canon appearance in this early version from the mid-1980s, which also features, as was common in the artwork of the time, an aerobics-inspired sweatband for Kit’s head. She does not look pleased about it.

Kitiara was a human who was the childhood friend, and sweetheart, of Tanis, the half-elf hero and perhaps main character of the books. The passionate yet unprincipled daughter of a mercenary, she rose through the ranks to became an evil-aligned dragon Highlord, riding a Blue Dragon (second only to the Red in the AD&D universe) named Skie. One of the original series’ highlights was her seducing Tanis in enemy territory near the huge, churning whirlpool known as the Blood Sea.

Kitiara has an anger management problem

Kitiara was the only female dragon Highlord in the original trilogy. Her most heinous acts were against Laurana, her rival for Tanis’s affections. As such she served as the typically jealous ex-girlfriend, a trope that was problematic for me. But then, the books are not known for being high literature, or even good examples of fantasy literature. They were very popular however.

At the end of the series and its many sequels, it was revealed that Kitiara was yanked down into Hell by Lord Soth, a rather ignoble end for such a strong female character. I can’t help feel that authorially it was a kind of punishment for a woman reaching beyond her station. The other notable female characters in Dragonlance, in contrast, did not ride dragons, although one WAS a dragon. But that’s different.

For fantasy artists in the 2000s and 2010s, female dragon riders are more popular than ever before.

Dragon Lady by HappySadCorner

Dragonrider by A.A. McConnel

Peacock Dragon, by David Revoy

Dragonrider by Max Yenin

Now let’s move on from women riding dragons — which may be interpreted as women owning and controlling their dragonish natures — to woman AS dragons. In Greek myth creatures like Scylla, Echidna, and Medusa had monstrous or dragon-like aspects, as did Grendel’s mom from Beowulf. Norse myth spoke of the dragon Nidhogg that gnawed at the roots of the World Tree Yggdrasil. And of course, there’s Lilith and Tanit/Inanana/Ishtar. They have over time gone from being creatures of power to being cursed and outcast.

In Western fantasy literature fairy tales formed the bulk of dragon transformations up until this century. One of the most typical is the ballad The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh. An evil Queen, jealous of the beauty of her stepdaughter Margaret, turns her into a dragon. When her brother Childe Wynd returns from overseas, Margaret tells him that to break the spell, he must kiss her loathsome form. Unhesitatingly, he does so, and she turns back into a human. Together, they overthrow the Queen.

This is an Arthur Rackham illustration I remember well from a book of fairy tales I had as a child. Arthur Rackham can be thought of as the inspiration for Brian Froud. I think he intended this dragon-serpent to look repulsive, but she’s actually pretty cute with her nose in the air.

In this pic the Lady Margaret is emerging from the skin of the worm, or wyrm, in a manner similar to St. Margaret who may have been her inspiration. But unlike St. Margaret, she is saved by the dedication of a man and not God. Actually, it’s more than dedication. It’s a willingness to face the dark and unpleasant things in life.

A dragon masquerade in the 1910s.

In the 1960s Disney animated cartoon Sleeping Beauty the villainess Maleficent makes a powerful inspirational turn when she transforms into a dragon to thwart Prince Phillip. I think it’s the first time “Hell,” that most minor of cuss words, was uttered in a children’s movie.

What this says as a myth about gender relations is interesting. Aurora and Maleficent can be argued to be two sides of the same woman. The pretty, feminine, submissive Aurora sleeps; the active, evil, powerful Maleficent guards her and prevents her from waking. When the Prince comes, Maleficent pours all her wrath into fending him off. Yet in the end she is defeated, and Aurora woken with a kiss, and taken away into traditional married life. It can be read as an indictment of women’s lives in the 1960s, where they were expected to give up their autonomy and power to be traditional wedded wives. But perhaps it can also be read as a sexual awakening, where a woman’s fear must be defeated for sexual unity and enjoyment to take place. The movie was made in 1959, on the cusp of the 1960s and its social changes. It seems to predict the battle of the sexes. If Prince Phillip symbolized the traditional roles, he won the battle but lost the war.

In Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Tombs of Atuan there’s a similar situation, described by the author herself as “puberty” where Tenar has the power to kill and defeat Ged, yet restrains from it because of her pity and fascination. She gives him water and the directions to get out of the labyrinth, and he later emerges to be the cause of an earthquake that collapses much of Tenar’s old home and whisks her away to become “The White Lady” in the inner archipelago, a traditional patriarchy where she is to be powerless, yet exalted, in a fine silk gown. Was I the only one who felt let down by this ending?

Over the decades Maleficent has gradually become the apex Disney villainess and something of a role model for many modern women for her evil glamour and ruthlessness. She is so popular she even received a retcon in the 2014 movie Maleficent, with Angelina Jolie in the title role. Disappointingly, it’s her henchman that turns into a dragon, not Maleficent herself, but she does have a pair of horns and hooked, dragonlike wings.

Dragon women also received a strong boost from the 1984 American TV show V, which had the Earth conquered by a race of reptile people who masqueraded as benevolent human overlords. Two of the most prominent were Diana (Jane Badler) and Lydia (June Chadwick), commanders of the invading “Visitor” forces. Described as chaotic evil and lawful evil, respectfully, they paraded around in form-fitting uniforms and did naughty things like eating live mice. The show was a turning point in SF. Up to that point, women had not been portrayed as leaders in SF worlds; even Star Trek: The Next Generation, for all its fanfare and emphasis on diversity and equality, still had male captains. The two powerful lizard women inspired a lot of frenzied wish fulfillment for girls of that era.

Behold the awesome, futuristic plywood console for advanced spaceship navigation.

It seems the rock band KISS was an influence on the costume designers of the show. In the photo above Diana’s uniform bears a distinct resemblance to Ace Frehley’s Space Ace getup, and in one episode the ladies even don a variant of his facepaint. Tragically, the full-blown lizard prosthetics were rarely shown, and then only in pieces.

It seems the rock band KISS was an influence on the costume designers of the show. In the photo above Diana’s uniform bears a distinct resemblance to Ace Frehley’s Space Ace getup, and in one episode the ladies even don a variant of his facepaint. Tragically, the full-blown lizard prosthetics were rarely shown, and then only in pieces.

In the years since V, other Dragon girls have cropped up in unlikely areas. In the comic world, for example, there is a zaftig character called She-Dragon, who seems like a She-Hulk knockoff.

With the rise of the internet, it became easier than ever for SFF artists to scan and share their work, and fans to share artwork and fiction too, and their fantasies, and find connection with other fans. That’s how Furries founded a subculture. Furries are folks interested in humanoid and anthropomorphic animal characters as creators of artwork, fans, or roleplayers. Deviant Art, founded in 2000, became a major online site for Furry connection and artistic critique. The most popular Furries have traditionally been the glamourous ones like big cats and wolves, but as with fanfic writers, artists continually push the barriers of what is possible, and thus, Dragon girls were born… sexy, dangerous, creatures of fantasy.

Artwork by Khary Randolph

Charizard by Atryl

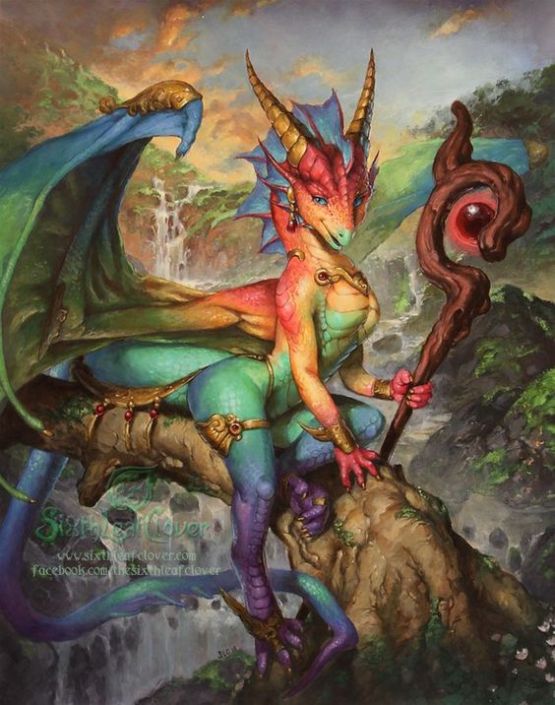

Prism Magic by SixthLeafClover

V Save Alien Lover by Vladcorail

The Wrong Damsel by Oddmachine

So we have come full circle over thousands of years. Dragon September is over. It’s been fun!